| Forensics Home |

|

Why real forensic science isn't like the TV

(but can I have a signed picture of Jorja Fox anyway please?)

I was a forensic scientist in the UK for eighteen years. I'm hoping to remain one, but that remains to be seen. Unusually for my profession though, I did tend to watch some of the forensic-based shows. I say did, because the only one I still watch is NCIS, and that's only peripherally forensic. I should make it clear that in general I'm not criticising these shows (except where I clearly am) because I understand that issue of dramatic licence etc, and keeping the audience interested. Most of my colleagues can't watch as they spend the whole time looking at all the thing the TV gets wrong, or misses out, or exaggerates. A better way of understanding what this article is about is: I want to show readers what exactly has been left out in that dramatic licence. This is particularly for people thinking of moving into this area of work, and what to know a bit more about what it's like in the real world.

Lets get the TV criticism out of the way first

Regardless of any issues I may have with the job side of these series, I thought I'd just get in my criticisms of them as TV drama. I loved CSI: Vegas, at least as far as the end of series five and the vastly-over-rated Tarantino double episode. The characters were well-rounded, and stayed in character, not the lazy way for screen-writers where plot drives character (compare and contrast the first four series of The West Wing with the last three to see the difference). I really never understood the fuss about this story though. I've heard it said that all the actions of the characters were based on things that we have already learned about them in earlier episodes; but it never felt like it: it felt like a well-understood group of people had been taken over by a puppet-master and made to do a completely new dance. Any remaining interest vanished when William Peterson bailed out.New York was OK, but I lost interest about the end of series three. To be fair, it's very rare for me to last beyond three series of any TV program. In fact, I can't think of a single series longer than five seasons where I watched all of it. Sometimes I was late in and never caught the beginning, but usually I spotted the shark had been well and truly jumped and stopped watching. With CSI with was the aforementioned leaving. David Caruso ruins the otherwise good Miami and I gave up about series three again. But this is not a TV review, so on with the forensics.

I'm not even going to talk about Waking The Dead because it's so bad. Not just at forensics, which it doesn't even try to get right, but at being a drama. Anyway, on with the bits that really aren't like TV.

Specialisation

On TV, everyone is an expert in everything. The same scientist will do blood patterns, DNA, drugs, explosives etc. Everything in some cases. At best someone might be considered good at everything, but maybe an expert in one field (say, insects). In real life this is rarer, with the vast majority of forensic scientists only working in a couple of areas, usually (but not always) related. In my case for instance, I analysed controlled drugs. But in things like powders, liquids and tablets because I wasn't trained in drugs in body fluids. I was also trained in comparison of packaging. That's it. It's a bit like doctors or surgeons: GPs know a bit about everything, but seldom a lot about one thing compared to other single-discipline doctors; and surgeons tend to be experts in one area, with only some doing general surgery. And no prizes for guessing who is best in a particular area. Yep, the expert in that field. If you need brain surgery, you really need to insist on the work being done by a brain surgeon, not a general surgeon trying to keep his hand in. And so it is in forensics: the depth of knowledge required to be a master in one field seldom leaves enough time to become master in more than about one other, except where fields are closely related. Although it should also be pointed that different cases require different levels of expertise, and in many cases a generalist might be able to do the work. But still not as well or as quickly as an expert. This is one of the downsides of the US model of forensics where every state has at least one lab, and sometimes every county has one. These labs tend to be on smaller budgets and thus with limited staff numbers. Here, cross-training is more likely. But the fact that it is a necessity born out circumstances doesn't make it a good idea. Pretty much every other country on Earth has a small number of labs serving the whole country, and much more specialisation, and for good reason: experts always trump jacks-of-all-trades. But of course a real lab doesn't have to worry about the length of the cast list, and the cost of all those extra speaking parts.Paperwork

There is lots of paperwork in forensic science, but almost never on TV. Lots and lots of paperwork. When you watch CSI, it's rare for anyone to write notes, for instance. Or type them for that matter. But real forensic scientists write copious notes. forensic science is slowly becoming electronic, but for many reasons the old-fashioned way works better on most cases. I may talk about this elsewhere at some point. In fact, scientists can spend as long writing notes as they do actually examining things. This has got a lot less onerous in the last few years, with the advent of widespread digital camera use, but it's still a big part of the job. At the absolute least, you will need notes on the packaging (for continuity), the item, the analysis, any special analysis if you didn't follow SOPs. More complex work may need yet more notes on how item were compared, what was found, and what it means. It's important to remember that it will usually be months until the trial from when you take those notes. A practitioner needs to be able to open the file eighteen months after they wrote those notes, and not only be able to understand what it all mean, but be able to answer questions in court about the case. Now pictures of everything certainly help, but they need annotating at the very least.Then there's all the company paperwork. This is more true of those forensic providers operating as commercial enterprises (a slippery slope that the UK is sliding down as we speak), but is at least partly true of all. You will probably file a copy of the final report, as well as sending one to the customer. There's all the instrument printouts if you used analytical equipment, copies of transfer documentation within the organisation and out of it (of which, more later). If you are a commercial company, there's time sheets and bills. Etc. All this takes time to fill out, and most will be dine by the scientist. I would expect more to be generated automatically as time goes by, and systems get more integrated. But the forms still need to be filled in. Just as an example, a typical one item cocaine possession case dealt with by the Forensic Science Service (RIP), who I worked for, might well have over fifty pages in the file, depending on the level of analysis. Complex murder case might run to several box files. You can imagine how much time was spent writing (or even printing) all that.

Caseloads and Priorities

On TV, everyone only seems to have one case to work on: I'm still waiting for Abby to tell Gibbs that his new case is less important that the other forty-three cases of his that she is already working on. Exact work loads will vary from lab to lab around the world, and so will methods for parceling work out. It may even vary within one lab. But most labs have a system where any given scientist will have several cases on the go at the same time. "On the go" is, of course, relative: they may have file, and date when the case must be finished, but not actually be doing any work on those items. "Multi-tasking" is seldom really that: "task-swapping" is a much more accurate description outside of a few bits of computing. So the scientist can only concentrate on one case at a time. If they are waiting for work from other people, clarification from the police (and police officers only submit items just before spending three weeks away from the office) or something, then they may fill in with a different case. Then that grinds to halt as they wait for a gel run, so it's case number three, and so on. Talking of which, I remember one CSI case where Sarah announced that she would wait for a DNA run which had just been loaded. Good luck with that, it's about six hours, even these days. But on TV there's never any real waiting, and only one case ever seems to progress at a time. I appreciate that murder cases - the main plot subjects - get priority, but a murder gel run is the same delay as a burglary one.I'll also just mention that TV doesn't usually have the boss coming around the lab twice a day to ask whether case x will be finished by the official delivery date. And it doesn't have annual performance assessments where quality of work comes a poor second to output figures. I'm not sure how much the latter are a factor overseas, but they are major parts of forensic work in the UK.

Money and Costs

Although the UK is only country I'm aware of which has tried to completely commercialise forensic science, the sad fact is that money (and avoiding spending it) is an important part of forensic science across the world. There probably are some labs where the scientist just does what they think is best and hang the expense, but there certainly aren't many of them. In all the real world labs I'm aware of, costs are a major issue. Essentially, the name of the game is to do the minimum amount of work which will get you a result which will stand up in court. And to do that work in the cheapest possible way. I am not saying this is wrong, but I think it might be the wrong way to approach it. I don't want to get too involved in this issue here, because I plan to go into more detail elsewhere, but on TV I've never seen a boss tell a scientist to not use a test because it costs too much. But I accept that murder budgets tend to be much bigger than for other crimes -and rightly so. Or seen scientists argue about whether a further test will help enough to justify the outlay. These are common bits of real forensic science.Seriously: just no

Even in the US, to the best of my knowledge forensic scientists do not do much work outside of the lab. The do on occasion attend scenes (although in the UK this is mostly handled by SOCOs, who now insist on being called CSIs) but that's about it. That means no going around to people houses to ask them questions (police job), no getting into gun fights (police job, and few scientists carry guns) and no interrogating prisoners (police job). Although I have to admit that were many times when you wanted to shout at a suspect: "What were you doing?" Or more usually: "What were you thinking!" Some do attend autopsies though, as a lot can be learned from the exact details of wounds etc. Sadly, in the UK at least, we don't drive Hummers.Contamination

Some years ago, a much-respected colleague of mine was in the US giving a talk (on blood pattern analysis I think, if anyone cares) which he illustrated with slides from various scenes. A US policeman wanted ask a question: "What are those weird white suits everyone is wearing?". The "white suits" are Scene Suits, AKA "Bunny Suits" which are worn by everyone visiting a crime scene in the UK, or at least any major ones. (Another colleague once used one of those suits and some paper plates to make a Dangermouse costume for a Fancy Dress party...) As my colleague pointed out, they are to avoid the scene contaminating the scientist and vice versa. This is one bit where CSI et al are fairly accurate. But sadly, the practice they get correct really needs to be changed: I gather that it is still common for police and forensic scientists in many countries to deal with scenes with only latex gloves as an anti-contamination measure. Noooooo...To be fair, the programs will discuss cross-contamination (which is no-where near as common, or likely, as the Defence might have you believe) on occasion. But just now and again I'd like to see them gowning up and scrubbing the lab clean, even behind and under all the furniture. Or at least intimating that it has been done - because it is.

Equipment

One of the many joys of being a real forensic scientist (and a picky one) is realising what marvelous equipment TV forensic labs have. CSI does this best. In that lab, they have a single piece of equipment, an Agilent Technologies 6890/5973 GC/MS. But what a machine - not only can it analyse anything - drugs, paint, metals, explosives etc - but it can even provide a DNA profile. Every lab should have one - our poor labs needed GC/MS, NMR, XRD, XRF, and a whole suite of DNA stuff to do all that. And some things we couldn't analyse at all - when was the last time you saw CSI people say: "I'm sorry Gil, but I've no idea what this stuff is"? In fact, this happens surprisingly often in real life. There are a lot of elements and compounds in nature, with a total in the tens of millions. Obviously some of these are much more common than others, and thus are more likely to be identified. But other factors are present as well. Can you even analyse it? Some things require very specialist equipment, other can just, well, go down a GC/MS. Sometimes there's no reference for the material, so without a library copy then you probably can't identify it - and you'll certainly struggle to prove it in court.Mind you, advanced as the hardware is, they seem to have forgotten to buy any software to control the autosampler (the word "auto" should be a clue), because the cast always load the sample straight into the carousel and then press the "Start" button the GC control panel. Normal mortals use the computer and the sequence it is running, and place the vial into the tray. The big one, with about a hundred positions for samples. As I said earlier, it's not just your one case on the go. Of course I understand that's it's just an excuse to show the actor doing something scientific. One problem: the difference between someone who has done something like operate a pipettor a few times, and someone who has done it hundreds of times is usually pretty obvious - at least to peoplein the latter group. We do these things much faster, and in a far less stilted manner.

Finally, no-one, and I mean no-one, uses the expression "Gas Chromatograph" in a real laboratory. "Mr Mass Spec" is within the bounds of possibility though - see One Last Thing... below). At least outside of a court when you have to explain the technology. It's a GC. In fact, the equipment these programs use is a GC/MS (and we just say the letters without mentioning the "/"), or just "mass spec". Technically the "mass spec" but is just half of it, but it's the important bit. Given that any of the audience who doesn't know what a GC is (or a GC/MS) will be none the wiser if you use the full expression, it seems silly to use the full word. Unless it's for the hilarious out-takes video as they keep getting it wrong.

...and results

The other thing I like about this wonderful machine is the fact it only seems to have one result: a mass spectrum for cocaine. I first noticed this on CSI: Vegas where it was used, in different formats, in at least three episodes. Later on it turned up in NCIS, and I'm sure I've seen it in other series. I've seen it described as the results of an an explosives analysis, a metals analysis (which you can't do on most mass specs) etc. But it's actually a cocaine spectrum. I've seen that spectrum thousands of times and would recognise it - as I in fact did - even without the figures on it (the fragment weights). Once I froze the picture to take a close look and could just make out those weights. Yep, definitely cocaine. I can only assume that there's some sort of in-joke going on here. Again, given that most of audience has no idea what they are seeing, why keep using the same thing? At least give us a heroin spectrum now and again or something.I hope I don't have to point out that not only do different machines produce different types of result, but often two similar types of machine made by different companies will produce different-looking paperwork. More so if you are running any kind of custom results software. I should also point out that results always need to checked by a person trained and authorised to do so. This is an absolutely fundamental rule of forensic science: check everything. But it's a bit dull for TV, so the only time you see checking is so that character B can point out a mistake to character A. I'll gloss over those times in real life when the only person authorised to do that checking is out of the office, so that you now have to wait until tomorrow for your results to be given back to you.

It's Always Identical Unless it Isn't

This is the one bit where CSI and the like get forensic science most wrong, and it's the bit that causes most problems in court with the "CSI Effect". On TV, a result is always a case of "they are identical" or "they are different". But real forensic work is almost never that simple. Mostly, it's all probabilities. Now people are used to the odds quoted in DNA cases (although they are always quoted in the wrong way, but that's a whole other story), but the TV never make clear that just about all results are like that. The only difference is most don't have actual odds, because they are no data tables to give those figures. Scientists just use expressions like: "Very likely" and "very unlikely", and all points in between. I can say that it's likely that this plastic bag comes from that stock over there, but I can't say that it is certain that it did so. I can say it is more likely than not that this screwdriver left those marks on that window, but that's as far as it goes. But a generation of jurors think that everything is just so, and can't understand why the scientist in the witness box won't just give a statement of certainty. This is one part of forensic TV where the licence that they take is actually harming the criminal justice system. God knows the jury often struggle with scientific evidence, and this just makes it more likely that they will acquit just because they expect the evidence to say more than it can, or ever has done.And it gets worse: sometimes results are similar, but it really doesn't matter and little evidential value can be gathered from the result. If I find a fibre which matches your trousers, then how much this matters as evidence is clearly related to how common your trousers are: if 10% of the population have a pair it matters far less than if 0.01% have them. This is more with some evidence types than others though: footprints are generally related back to a particular piece of footwear, for example, not to a model (except for screening purposes). But many other things, like fibres, can only be compared back to a type.

I should just point out the one exception to the above: "physical fits". This is the bit where the spy takes out his half of the torn $10 bill and puts it together with to the half his contact has. That's a physical fit, and in the majority of cases it is conclusive: there is no question but that object B was once part of object A.

One Last Thing...

Life in a forensic lab does not consist of a group of miserable people sitting around being miserable (shut up, ex-colleagues). As with any other workplace, there's fun to had, much of it tasteless. There was a running joke in our team how much we really did not want a fly-on-the-wall documentary team at work - there really would have to be a lot of explanations about some of the jokes, and the fact that they actually were jokes. Forensic science also seems to contain a disproportionate number of weirdos as well. No one is sure whether it's a prerequisite of the job or a result, but either way you frequently end up with people whose personality axis is displaced a few degrees from x,y. Especially if they deal with firearms or drugs.There is some of this in some of the programs, but nowhere near as much as in real life, where trivial banter and random personal abuse tend to massively outweigh serious scientific discussion. By far the most accurate look inside a real lab I have ever seen was in the original Prime Suspect. I had heard that Lynda La Plante had visited genuine forensic labs, and the brief bit inside one on the TV showed it. After the police have finished talking to the eccentric scientist (slight note: police are generally not found in the lab area, no matter how important the case - see "contamination" above) the camera pans around to two other staff who are busy gossiping about a colleague. Totally accurate.

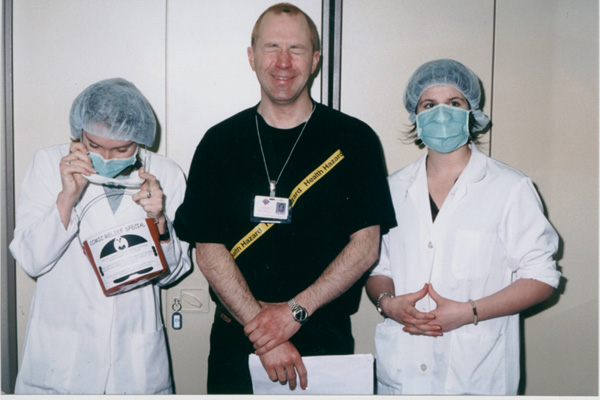

So here are some forensic scientists being very serious (if for a good cause):